For decades, a job has been seen as the key to escaping poverty. A major new study turns the question on its head: What if hardship is the result of employment, as opposed to the absence of it?

The American Job Quality Study, a survey of 18,000 US workers published earlier this month by the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, is the most comprehensive picture of job quality ever produced. And the results are not pretty: Just 40% of Americans say they have a “quality job.”

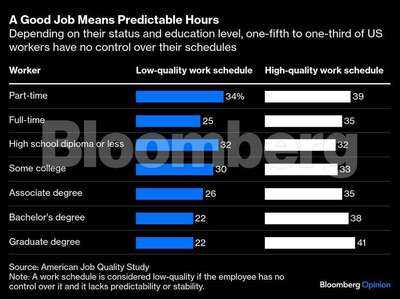

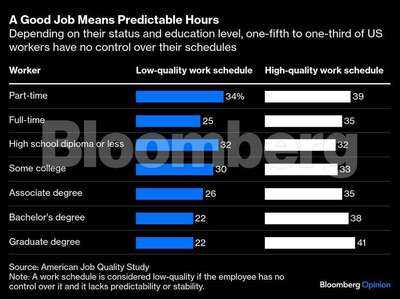

No doubt many workers will shrug this off as obvious, if not an underestimate. Employers, meanwhile, will probably greet it with their own shrug of doubt and denial, saying their employees are surely not among the 40%. What jumped out to me, however, is a key finding on which that figure is based: 62% of workers do not have a say over their schedules.

It is yet another piece of evidence showing that the US labor market produces unstable, volatile earnings, which are harming a growing number of workers and their families. There are some obvious and tested ways to address this problem — and the main obstacle to carrying them out is not so much political as historical and intellectual.

In 1962, Michael Harrington’s The Other America, a portrait of poverty in the US, was published. One aspect of its thesis became conventional wisdom: The poor are a permanent underclass that live in isolated, depressed communities. His book spurred the War on Poverty and shaped the design of many of America’s social welfare programs.

His legacy, frankly, is too influential. Longitudinal studies of family income in the 1970s and early 1980s show that, while long-term poverty exists, it is a slim, fractional minority. Poverty is a mostly transient state experienced by a much larger share of people and caused by household and/or labor-market disruptions. Poverty isn’t a function of where you lived or how wealthy your parents are. Income can drop for lots of reasons: Someone moves out of the house, a job is lost, an accident prevents someone from working full-time. A new job, or recovered earnings, can end the spell.

Of course, politicians interpreted these results as crudely as you might expect. They ended cash welfare in 1996, adding stringent work requirements and time limits while making no changes to the structure or rules of the labor market.

Meanwhile, the economists continued their research. Longitudinal studies of family income in the 2000s and 2010s show volatile income and earnings pushed income above and below poverty levels. A study of annual incomes between 2007 and 2018 finds that 40% of households spent at least one year out of 10 in poverty. A study of monthly income between 2013 and 2017 finds that, in any four-year period, a third of Americans would experience at least two months in poverty.

Then came the seminal US Financial Diaries Project, published in 2017. A daily accounting of income and spending in low- and moderate-income households, it revealed not only the extent of income volatility, but how much of it was attributable to work. If the lesson 40 years earlier was that poverty came from disruptions to work that caused a drop in income, the diaries made clear that work, undisrupted, can cause drops in income. Individuals were steadily employed, but because of erratic schedules or the nature of their contracts, their earnings fluctuated wildly — even in the same job.

And they didn’t like it. When participants in the study were asked whether “financial stability” or “moving up the income ladder” was more important, 77% chose stability. Let me say that again: The vast majority of people would rather have predictable income than more income.

In the past few years, researchers have studied the source and extent of unstable earnings. A key source of instability is work schedules: a growing share of workers do not get even a week’s notice about when or how much they will work. Another source is the “gig-ification” of wages, where being paid for time is replaced with being paid for service. This exposes the worker, instead of the employer, to fluctuations in customer demand.

In the past few years, researchers have studied the source and extent of unstable earnings. A key source of instability is work schedules: a growing share of workers do not get even a week’s notice about when or how much they will work. Another source is the “gig-ification” of wages, where being paid for time is replaced with being paid for service. This exposes the worker, instead of the employer, to fluctuations in customer demand.

The consensus among economists today is that the majority of workers in the US have income that changes month-to-month in an unpredictable way. So the American Job Quality Study is both unsurprising and significant. Almost every study of instability shows that it is more likely and more pernicious for lower-income workers, and that it creates financial stress and hardship, including episodic poverty.

And there’s a low-cost, low-risk fix: updating labor regulations to cover scheduling and pay. Employers will claim it will be costly and may lower employment. But the churn of unpredictability causes high turnover and lower productivity, while scheduling regulations raise productivity and do not cause job loss.

The continued expansion of work requirements — the budget signed into law last summer imposes them on Medicaid recipients, despite overwhelming evidence they don’t work — shows that politicians and policymakers still cling to an outdated notion of poverty, the “otherness” of 1960s thinking. As House Speaker Mike Johnson said earlier this year: “You know, work is good for you. You find dignity in work. And the people that are not doing that, we’re going to try to get their attention.”

If only 70 years of accumulating evidence on work, income and hardship could get his or Congress’s attention, the lesson would be clear: Instead of requiring people to work, Washington should require work to be better.

The American Job Quality Study, a survey of 18,000 US workers published earlier this month by the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, is the most comprehensive picture of job quality ever produced. And the results are not pretty: Just 40% of Americans say they have a “quality job.”

No doubt many workers will shrug this off as obvious, if not an underestimate. Employers, meanwhile, will probably greet it with their own shrug of doubt and denial, saying their employees are surely not among the 40%. What jumped out to me, however, is a key finding on which that figure is based: 62% of workers do not have a say over their schedules.

It is yet another piece of evidence showing that the US labor market produces unstable, volatile earnings, which are harming a growing number of workers and their families. There are some obvious and tested ways to address this problem — and the main obstacle to carrying them out is not so much political as historical and intellectual.

In 1962, Michael Harrington’s The Other America, a portrait of poverty in the US, was published. One aspect of its thesis became conventional wisdom: The poor are a permanent underclass that live in isolated, depressed communities. His book spurred the War on Poverty and shaped the design of many of America’s social welfare programs.

His legacy, frankly, is too influential. Longitudinal studies of family income in the 1970s and early 1980s show that, while long-term poverty exists, it is a slim, fractional minority. Poverty is a mostly transient state experienced by a much larger share of people and caused by household and/or labor-market disruptions. Poverty isn’t a function of where you lived or how wealthy your parents are. Income can drop for lots of reasons: Someone moves out of the house, a job is lost, an accident prevents someone from working full-time. A new job, or recovered earnings, can end the spell.

Of course, politicians interpreted these results as crudely as you might expect. They ended cash welfare in 1996, adding stringent work requirements and time limits while making no changes to the structure or rules of the labor market.

Meanwhile, the economists continued their research. Longitudinal studies of family income in the 2000s and 2010s show volatile income and earnings pushed income above and below poverty levels. A study of annual incomes between 2007 and 2018 finds that 40% of households spent at least one year out of 10 in poverty. A study of monthly income between 2013 and 2017 finds that, in any four-year period, a third of Americans would experience at least two months in poverty.

Then came the seminal US Financial Diaries Project, published in 2017. A daily accounting of income and spending in low- and moderate-income households, it revealed not only the extent of income volatility, but how much of it was attributable to work. If the lesson 40 years earlier was that poverty came from disruptions to work that caused a drop in income, the diaries made clear that work, undisrupted, can cause drops in income. Individuals were steadily employed, but because of erratic schedules or the nature of their contracts, their earnings fluctuated wildly — even in the same job.

And they didn’t like it. When participants in the study were asked whether “financial stability” or “moving up the income ladder” was more important, 77% chose stability. Let me say that again: The vast majority of people would rather have predictable income than more income.

In the past few years, researchers have studied the source and extent of unstable earnings. A key source of instability is work schedules: a growing share of workers do not get even a week’s notice about when or how much they will work. Another source is the “gig-ification” of wages, where being paid for time is replaced with being paid for service. This exposes the worker, instead of the employer, to fluctuations in customer demand.

In the past few years, researchers have studied the source and extent of unstable earnings. A key source of instability is work schedules: a growing share of workers do not get even a week’s notice about when or how much they will work. Another source is the “gig-ification” of wages, where being paid for time is replaced with being paid for service. This exposes the worker, instead of the employer, to fluctuations in customer demand. The consensus among economists today is that the majority of workers in the US have income that changes month-to-month in an unpredictable way. So the American Job Quality Study is both unsurprising and significant. Almost every study of instability shows that it is more likely and more pernicious for lower-income workers, and that it creates financial stress and hardship, including episodic poverty.

And there’s a low-cost, low-risk fix: updating labor regulations to cover scheduling and pay. Employers will claim it will be costly and may lower employment. But the churn of unpredictability causes high turnover and lower productivity, while scheduling regulations raise productivity and do not cause job loss.

The continued expansion of work requirements — the budget signed into law last summer imposes them on Medicaid recipients, despite overwhelming evidence they don’t work — shows that politicians and policymakers still cling to an outdated notion of poverty, the “otherness” of 1960s thinking. As House Speaker Mike Johnson said earlier this year: “You know, work is good for you. You find dignity in work. And the people that are not doing that, we’re going to try to get their attention.”

If only 70 years of accumulating evidence on work, income and hardship could get his or Congress’s attention, the lesson would be clear: Instead of requiring people to work, Washington should require work to be better.

You may also like

Tripura assembly delegation on five-day study tour to Gujarat

Jadon Sancho's career hits new low as Chelsea's £5million decision pays off

Charles Leclerc brutally taunted Max Verstappen in Mexican GP radio clip not shown on TV

Warning to anyone with a Gmail account as millions of passwords stolen

Monty Don reveals unlikely kitchen ingredient to help garden birds this winter